Big Mac McMyler Dumper on the CNJ at Jersey City New Jersey

Following is an article from a 56 year old Railroad magazine. It is an excellent

article explaining the workings of the McMyler coal dumpers at Pier 18

at Jersey City on The Central Railroad of New Jersey.

My copy of the magazine is physically falling apart

but I thought the information was worthwhile saving. The article was written by Ethne M. Kennedy

and photographed by Fullerton. It was published in Rairoad Magazine in the November 1951 issue.

It is presented here for historic and educational purposes only.

Home

|

|

BIG MAC is the Jersey Central's 32-year-old answer to one of the road's ever-present problems,

how to transfer coal speedily, safely and economically from harborside hoppers to the holds of waiting ships.

Astride Pier No. 18, a 900-foot quay extending into the Hudson River from the Jersey shore between Bedloe's and Ellis islands,

this giant coal loader can tighten its steel grip on a 100-ton car of coal, raise and upturn it so as to slide its sooty contents easily

into the broad pan of a telescopic delivery chute, and then dispatch the

empty hopper into adjacent yards-all in a matter of 50 seconds, if pushed to the test.

On the basis of physical layout or the employment of the most modern methods available,

Big Mac cannot be favorably compared with such postwar achievements as the Chesapeake &. Ohio's $ 8 million conveyor - belt

installation opened last year at Newport News, Va. Yet the millions of tons of coal poured out annualiy by Big Mac for the "Big Little Railroad"

discount adverse criticism on this score: Big Mac is doing more than the job for which it was intended;

under pressure it has adapted itself again and again to radical stepups in output without requiring any major changes in its initial design.

During a twelve-month period in World War II-1943, to be exact-Big Mac made shore-to-ship delivery of 19 million tons of coal. This was, of course, nearly four times its peacetime average, since the demand for coal even in the New York metropolitan area served by CNJ's Jersey City terminal is only seasonally heavy. In normal times the loader employing both its dumpers operates 20 hours a day in two 10-hour shifts during the winter; in the slack summer months one dumper is sufficient to manage the traffic while the second is being overhauled. The strain of winter operations is accountable for the large-scale repairs necessary each year. Behind Big Mac stands a crew of thirty-four. Seven of these are responsible for operating the dumper itself, while the remaining twenty-seven are outside men -brakemen, boat loaders, trimmers and the like. Indoors or out, these men find the winter as hard a grind as does Big Mac. From December 26th until Easter Sunday, they work on 10-hour shifts seven days a week, after which the pace eases off to permit a holiday per week. |

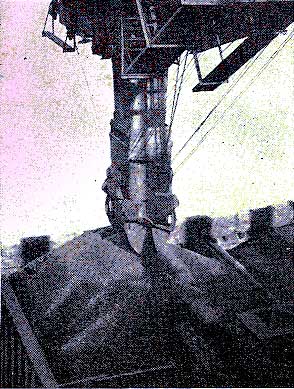

Big Mack's clam shell jaws open and coal roars through. Flow of black stuff is controlled from little house: operator can also swing dumper mouth North and South

, inboard or outboard of barge. Five section telescope will stretch from 9 to 45 feet.

Big Mack's clam shell jaws open and coal roars through. Flow of black stuff is controlled from little house: operator can also swing dumper mouth North and South

, inboard or outboard of barge. Five section telescope will stretch from 9 to 45 feet.

|

|

Yet this is not the complete

story. A bad storm like the blizzard of 1947 may so tangle up the yards that crews have to work round the clock to keep cargoes moving.

Pier Agent C. A. Roth remembers one time he didn't see home for four days, when he slept in a business car alongside the office track until

he had fought his way through the backlog of deliveries.

Yet Big Mac's crew leaves you in no doubt that the memories they share are worth the cost. Like Tom Cooney's picture of Pier Manager Wm. Flatley, a thick rope wound round his middle, stepping out onto the slippery steel pan below the windows of Big Mac's control tower, to hack away with a pick at the ton blocks of coal jamming the mouth of the coal chute, while the wind did its best to blast him off his feet and into the choppy river below. And just mention the night of December 26, 1947 and watch smiles spread across your listeners' faces. That was the night the snows began to fall, when engines beat their way across ice-blocked yards and cars were pushed downhill out on to the dumper lead with the hope that they wouldn't ride straight up to the top of the return ramp and out to sea. Fortunately for the CNJ and its clients no car has ever plunged off the kickback, but there have been several occasions when loaded barges sank at their moorings alongside Pier 18. And there was nothing the railroaders could do but watch them disappear, knowing they would be dragged up again days later. |

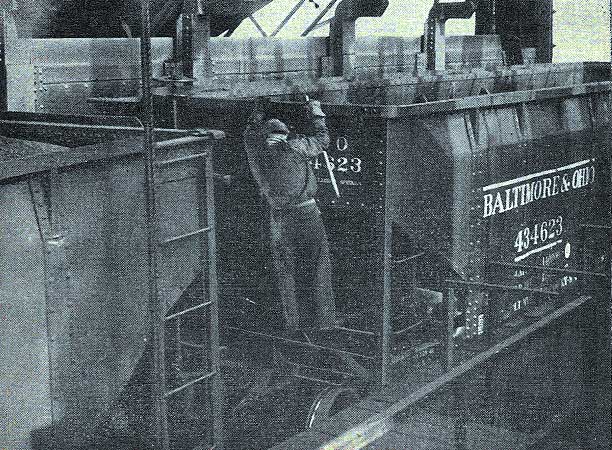

In the iron grip of Big Mac, a 75 ton hopper load of coal is overturned toward the telescope pan. Pier 18 is distribution point for Bridgeport, Providence,

Lynn, Salem and Boston as well as Greater New York.

In the iron grip of Big Mac, a 75 ton hopper load of coal is overturned toward the telescope pan. Pier 18 is distribution point for Bridgeport, Providence,

Lynn, Salem and Boston as well as Greater New York.

|

|

Since the transport of coal represents 26 percent of the Jersey Central's revenue and one-third of the total hauled goes over the road to New York

and its neighboring industries, it is easy to understand why Big Mac's activities are of prime concern to the owner. To keep hoppers moving to and

from Pier 18 without interruption, the Jersey Central terminal possesses the largest yard in the metropolitan area, with space for 2800 loaded cars.

In this it outranks even the Pennsylvania, Lehigh Valley, Delaware, Lackawanna & Western, Reading, and the Erie's harborside facilities.

Barges lining up at its dockside serve ports in Connecticut and Massachusetts as well as

NewYork, and during World War II some French and Irish freighters filled up with cargoes for markets abroad. All this

helps to make Pier 18 one of the most active loaders on the Atlantic seaboard. North of Philadelphia its rivals are

South Amboy (Rdg.), Perth Amboy (LV), Port Reading (Rdg.) and Hoboken Coal Docks (DL&W).

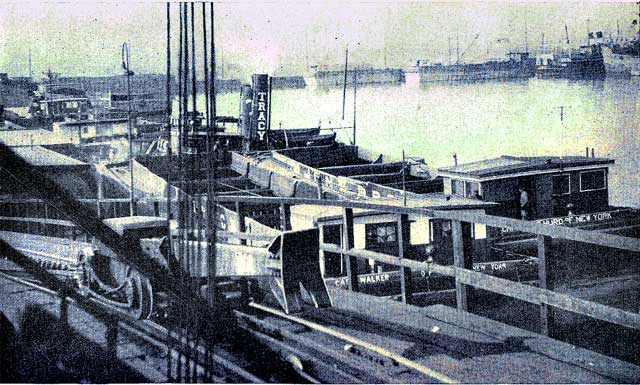

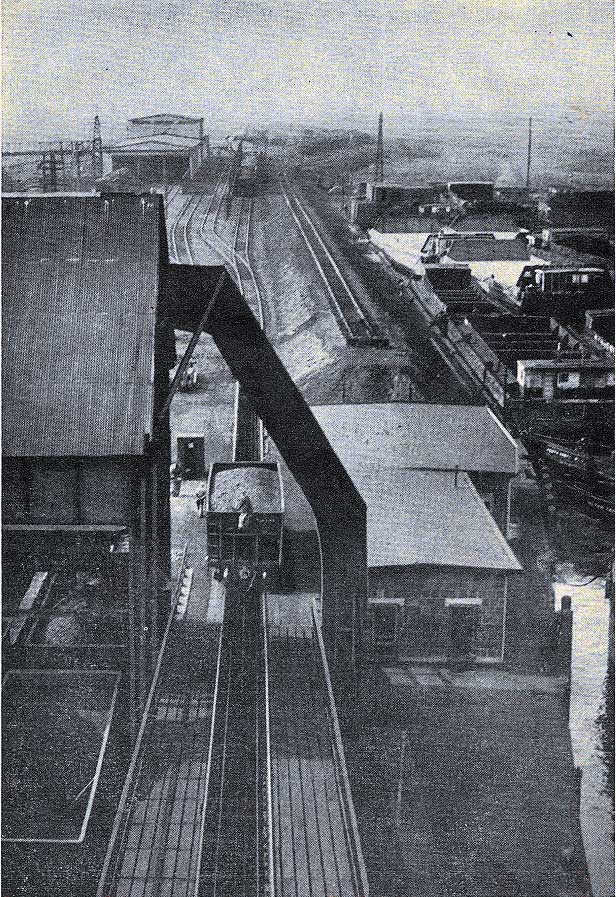

Against a backdrop of Manhattan skyscrapers, Big Mac's 90-foot structure is in no way remarkable. Climb up 55 feet to its control tower, however, and You'll find a vantage point high enough to provide not only a clear view of the proceedings near at hand but of the terminal's general plan. With your back to the Hudson, you look down upon nearly a hundred tracks. About a dozen of those straight ahead are lined up in the direction of the loader and these narrow to four as they approach the pier's end; two wooden sheds straddle six of them not far in the distance. To the left is a substantial brick building with a tall stack, obviously the powerhouse; tied up at the dock in front of it are several freshly -painted CNJ tugboats. To the right, barges of every description lie motionless in the protected river basin, while directly below a Tracy tug berthed between two scows impatiently blows off steam. Since the average day at Pier 18 sees the loading of from 21 to 24 barges, which vary in capacity from a Burns 72 holding 470 tons to one of Tracy's new 2040-ton steel leviathans, the adjoining basin always has occupants. Time meaning money both to the consignee and the carrier, schedules are kept tight, and to avoid delays there is mooring space for 80 vessels in the basin. As a rule not more than five minutes elapse between the departure of one boat and the arrival of the next. For the loading job does not end when the coal-heavy barge drifts off from the loading chute, propelled by a stiff wind or the pier-based motor. |

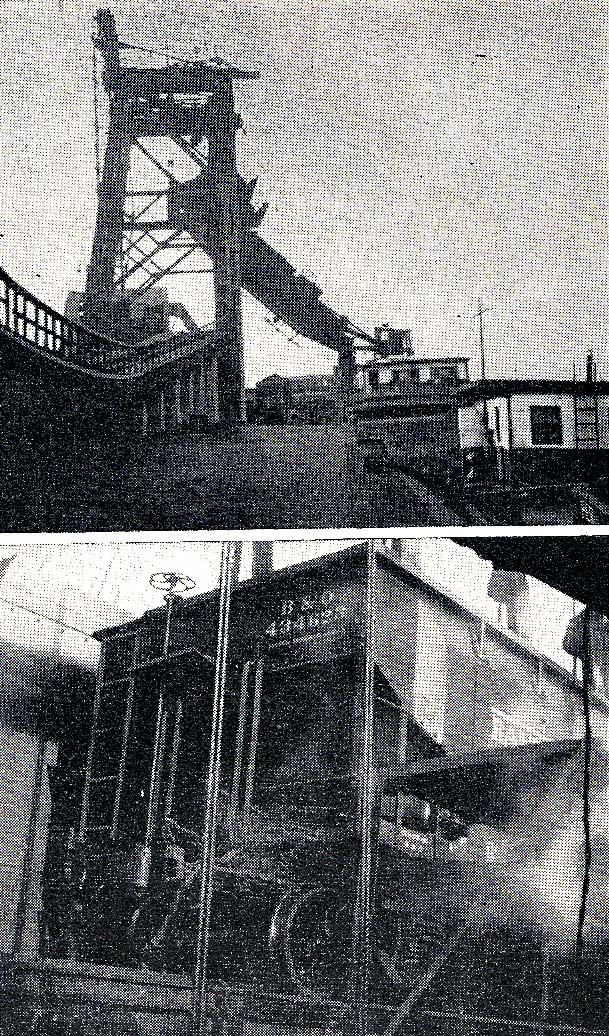

Gates of the hopper mouth are closed as Barge-load reaches capacity. "Trim" of scow has to be controlled carefully to prevent listing or overturning.

Gates of the hopper mouth are closed as Barge-load reaches capacity. "Trim" of scow has to be controlled carefully to prevent listing or overturning.

|

|

Before any vessel is deemed seaworthy, trimmers must level the loose coal and cover the hatches. Anthracite generally

runs swiftly into all corners of the hold but bituminous piles up and must be battened down before the vessel can safely leave the harbor.

Since carload traffic at Pier 18 is about equally divided between these two, you see a number of loaded barges docked nearby, awaiting trimming.

The eight-foot decks of old -time scows call for fifteen men to complete this wearisome chore. This is one reason why the design for new Tracy boats features a four-foot deck.

Below you is a weather-beaten scow christened The Hawk. Let's follow a load of coal from the yard into her hold and watch Big Mac in action. It is important to understand, however, that this McMyler loader, which performed its first day's work for the CNJ on July 1, 1919, is only the strong arm in a complex system of classification yards, thawing houses, steeply graded lead tracks and kickbacks, barneys and more. To keep coal flowing in a steady stream from the mines of Pennsylvania's Blue Mountains to CNJ consumers requires a combination of many efforts. Baltimore & Ohio, Reading, Western Maryland-these are the names most frequently stencilled on the hoppers ap-pearing in the Jersey City yard. Let's concentrate on B&O No. 434623-you will recognize it in a couple of the accompanying photographs and trace its trip to the dumper. Office arrangements having been completed, B&O 434623 rolls by gravity down the track leading to the barney pit, a brakeman riding the top to prevent a possible runaway. Once at the pit a long-armed barney takes over. Since this barney is controlled by Big Mac's tower, crewmen Brown and Tom Cooney enter the picture here. When Brown throws his lever. the eight-ton, counterweighted barney moves up behind the hopper, fixes a clefted ramrod against its coupler and then shoves the car up the steep incline to the loading platform. Steel cables grasp the hopper firmly. With a loud whining of gears We car begins to rise off the tracks in mid-air is held toward the wide open pan by which |

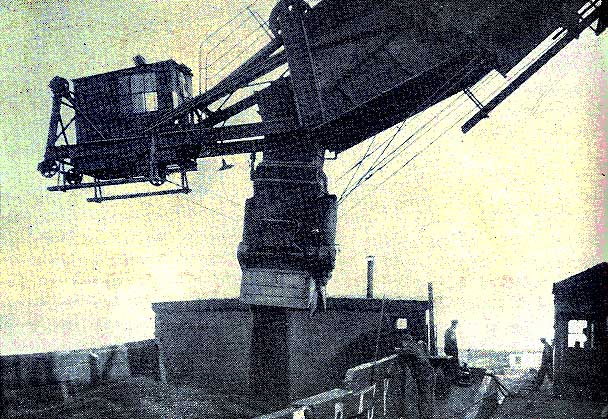

Left: Scene as McMyler Dumper overturns car pouring coal into telescope, thence to barge at dockside.

Left: Scene as McMyler Dumper overturns car pouring coal into telescope, thence to barge at dockside.

Below: Coal hopper on dumper cradle ready to be upended. |

|

Big Mac funnels coal into the barge below. To avoid unnecessary breakage, the car edge is brought right down to the apron or heel of the pan and the coal laid on.

Even with this precaution clouds of coal dust mushroom up as No. 434623 is completely overturned.

Without delay Tom Cooney pulls a release lever and the car is righted before it drops back to the track.

And while this B&O hopper was being put through its paces, the barney returned downhill

and is up now with another load. This latter gives the empty a push that heads it down the track toward the river, where 434623 mounts

a kickback giving it momentum enough for the journey back to the main section of the yard where it will be reclassified.

Although it's true that a 60- to 72-ton load of coal can be boosted up from the barney pit, hoisted into mid-air, dumped and then returned empty in 50 seconds, Big Mac's average is actually 20 to 25 cars per hour. One every two minutes is keeping them coming and going fast. The pressure for main-taining this schedule rests in good part on the towermen. A bit of poor timing could mean more than a poor showing; it could mean the breakdown of the dumper's equipment. So above the noises of river traffic and the constant vibrating of their cage, the crewmen call signals for one another. "Right," barks Cooney. "Right," responds Brown. Brown is in complete charge of the barney, Cooney the actual dumping, but their functions are inter-dependent. As a loaded car lists precariously toward the pan, Cooney's eyes watch for the block under the dumper. The moment it strikes the cable he presses for release. If he didn't, the strain might prove too great for the cables. Should one of them snap at this point in the operation, the second would not be sufficient to support a 100-ton car. The return trip is less dangerous. If a cable should break then the straight drop would be only a matter of a few feet. As a safeguard against accidents cables are checked daily. The pan cable is the largest; measuring about an inch and a quarter in diameter. Depending upon the time of the year they are installed, these can endure about a season's punishment. A cable put in during the summer may last until winter, while one set there in November may be worn out by the following January. Not much less vulnerable are Big Mac's pan and telescopic chute. The former is protected by a false bottom or wearing-sheets, composed of 3/4 -inch plates or steel; this lining is replaced annually. Two to three years of being scraped by frozen chunks of coal rubs the cast-iron telescope so thin that a new one is com-pulsory. Like the apron of the pan whict can be adjusted by a screw to compensate for changes in the tide and the varying heights of boats, the telescope is a most adaptable bit of machinery. Contracted it is nine feet long, but it can be stretched in five sections to a maximum 45 feet to meet the low levels of barge holds. |

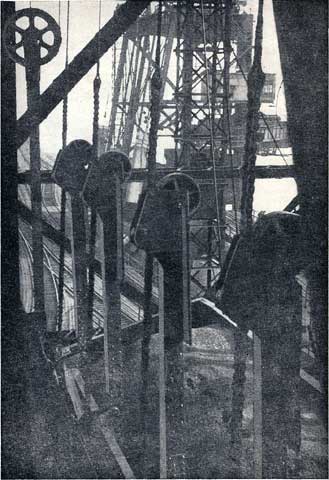

The kickoff. No. 434623 Gets the boot from loaded hopper brought up by tireless barney. Shove starts the empty rolling down the kickback,

which will give it momentum enough to ride back to the yards.

The kickoff. No. 434623 Gets the boot from loaded hopper brought up by tireless barney. Shove starts the empty rolling down the kickback,

which will give it momentum enough to ride back to the yards.

|

|

The pan of the dumper can hold 90 tons of coal. When anthracite is being poured, two carloads are dumped in the pan before the chute is opened.

This allows the anthracite to pass through in a steady stream, instead of beating itself to powder.

Breakage of coal, in a cargo valued according to a more or less uniform size, is a hazard. Another worry on Big Mac, fortunately only

a winter problem, is the freezing of carload lots into solid masses.

Despite the efforts of the thawing sheds, it sometimes happens during a severe winter that coal may topple out of hoppers in 10-, 12- or 15-ton lumps. There is nothing to do then but get someone to go out on the pan and cut these chunks down to size with a lance or a pick. The telescope pan is equipped with lances, though these are intended primarily to clean out the telescope should coal be-come lodged there. |

The hard working iron mule returns for another hopper to shove up the ramp. In background is basin in which 80 barges can wait thier turns

at the dumper. "Tracy" on tugboat stack is name of fleet which handles main cargo around Pier 18.

The hard working iron mule returns for another hopper to shove up the ramp. In background is basin in which 80 barges can wait thier turns

at the dumper. "Tracy" on tugboat stack is name of fleet which handles main cargo around Pier 18.

|

|

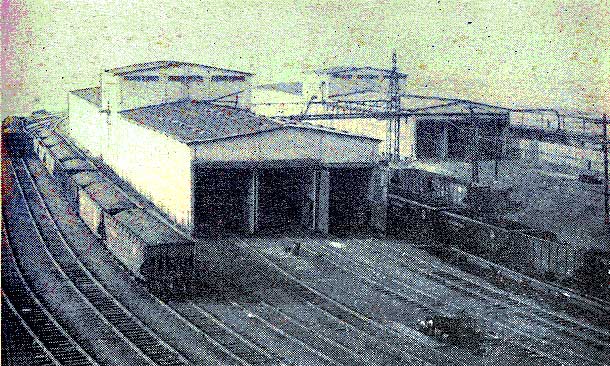

This drastic treatment is, however, the exception rather than the rule. During the cold weather cars enroute to the dumper

are passed through one of two cement-walled thawing sheds if there is any suspicion of frozen coal.

This usually occurs when the cargo consists of pea, buck-wheat, rice, barley and other fine coals.

Each thawing shed has three stalls long enough to hold eight cars. Inside there is a lance platform with 144 outlets from which steam and vapor can be directed into the frozen coal. A railroader uses a wooden mallet to hammer about eight lances into each car. These eight-foot rods are perforated at the bottom to allow jets of live steam to pour out where they will do the most good. Depending upon the size of the coal and the length of time the car has been exposed out-doors, thawing will require about an hour to an hour and a half. |

View from towerman's window with a car on the steep incline approaching Big Mac. A brakeman rides every car to the top and back into the yards.

View from towerman's window with a car on the steep incline approaching Big Mac. A brakeman rides every car to the top and back into the yards.

|

|

While this baking is going on, roller doors are let down at either end of the

shed. Within the temperature rises to 150-170 degrees Fahrenheit, for in addition to the lance openings

steam heat pours in through vents underneath the cars, which number about 50 per stall. These ducts are protected

against blocking by coal by wire screening. To create this inferno eight miles of piping were laid in each building,

and 12-foot fans make certain that the hot air is kept in circulation.

As might be expected the tremendous heat dries up the car journals. vVhen it is time to transfer the cars to the lead track, power is needed to start the stiff wheels rolling. Each shed track is provided with a steam winch for this purpose. Lying between the tracks, it can be linked onto the cars and force applied. Not until the hoppers are moving freely is the hook on the end of its wire cable loosened from the hoppers. One last precaution against trouble high up on Big Mac is the series of oil pits on Track 57 outside the defrosting units. The oil pits are used only in emergencies due to extreme cold. Then oil blowers can turn the heat on cars from either side of the track. The order in which loaded hoppers travel down Big Mac's lead is the result of careful yard reporting and office planning. Without this the Jersey Central could never offer the consignee the service it does. This involves not merely the meeting of barges on tight schedules, but loading them in whatever manner stipulated; and when it comes to packaging barges for market, coal merchants can be good salesmen. Thus Pier Agent Connie Roth receives orders for the loading of a barge with a large tonnage of a certain type of egg coal to be topped by a hopperload of Primrose, an exceptionally good run. Just like putting the choice berries on the top of the box. At present 72 shippers employ Pier 18 and their bills show a total of 370 types of coal. Although the U.S. Mine Institute would hardly recognize this number, CNJ's account books attest the fact. For on the carrier's records every grade of coal from every mine used by a shipper must appear as a separate class and be handled accordingly. This both complicates the bookkeeping and requires added shuffling when strings of loaded cars arrive from the mines. Sorting the hoppers in the classification yards is called "drilling coal" The first division is determ'ined by whether the cargo is anthracite or bituminous, which relegates the car to A or B yard, after which each consignee's cars are graded according to quality. Before a day passes a car, 'vvaybilled into Jersey City on a long drag, is ticketed by a car checker whose driller's check goes to the pier agent. Roth's office takes over then, notifying the shipper each day of the arrival of cargo. The next move is up to the dealer. Nothing more can be done until he phones the agent as to when his barge is to be loaded, giving in detail the type of coal, the tonnage and the name of the ship. CNJ submits a written report to its clients every 24 hours, individually noting the arrival of each car, with its weight, class of coal and from whence it's come. This statement forms the basis for demurrage charges should a client be tardy in carting off his cargo. Five days is the accepted limit for storing anthracite in the yards, six for bituminous. When an order does come through to get coal roIling, one of the desk men records the message and a copy of this order goes to Yard-master Penetti, whose shanty stands near the mouth of the yards and the entrance to pier trackage. The original is kept by the man handling the A or B account for the shipper. Penetti puts the coal on the hill, and so the cargo is dispatched to the waiting ship. The agent has a checker on Big Mac to record the numbers of the cars as they are emptied and meanwhile the cardboard tag from the driller has been put on file in the office. A tipple check comes from one of the yardmaster's men and the man on duty on the dumper turns in another when his trick is over. The two are compared, for they must tally with A or B records before the item is listed on the large yellow sheet controlling a shipper's account. At the end of the day a bill is forwarded to the consignee. |

The thawing sheds without which Big Mac could not operate in winter. Each stall holds 8 cars. Maze of tracks at Pier 18 includes 6 for classifying cars

according to which road or mine they are returning to.

The thawing sheds without which Big Mac could not operate in winter. Each stall holds 8 cars. Maze of tracks at Pier 18 includes 6 for classifying cars

according to which road or mine they are returning to.

|

|

With all the coal Big Mac pours out each day there are a good many carloads the dumper never sees, without which it would be powerless.

Winter and summer fires rage in the powerhouse furnace, consuming from one and a quarter carloads daily in off months to three cars daily when the rush is on.

Four boilers are worked all summer and twice that many in the winter to provide compressed air for the yards, main lines, dumpers and marine works,

as well as steam for the dumpers and the heating system.

In the powerhouse, too, are the wires which bring in AC current at 2300 volts. This current is then passed through transformers that step it down to 550 volts, when it can be converted to DC for use in the various motors on Big Mac and out in the yards. One vital draw upon this electricity is the two-way radio network linking Yardmaster Penetti's office with the far corners of his domain. Loud- speakers carry messages to the crews checking the cars, and microphones placed in the field make it possible for conductors to phone the dispatcher when their trains are ready to depart from Jersey City. This avoids considerable delay in the obtaining of running orders and makes possible the speedy dispatch of empty hoppers back to the mines. As long as there is coal to be mined and transported at a profit Big Mac will probably be kept busy lifting and dumping coal cars. Sometimes strikes have cut down its working hours, even halting operations occasionally; but such breakdowns only serve to emphasize its extraordinary adaptability. So far Big Mac's ability to stand up under burdens of increasing traffic and the pressures of wartime demands for fuel is a feat suggestive of one of railroad's greats -that mighty human, John Henry. Should Big Mac be scrapped tomorrow it would not change the fact that down at the railroad yards within shadow of the Statue of Liberty the mighty dumper is on its way to becoming a bit of a legend. The End |